Popsicles and number sense

One of my projects this summer has been to put together a

short course on calculating medications for care givers. This on-line course is

meant to help prepare pre-nursing students and others to safely prepare

medication doses based on prescribed amounts and drug labels. Why is this

needed? I hear repeatedly how anxious nursing students are about the math component of pharmacology and medication administration. I also hear from

parents, adult-children, and other family care givers that there are often

moments of confusion and concern when preparing doses for their family members.

Many very capable people experience moments of anxiety or self-doubt when required

to use math.

I have had my own angst about math that began during those

dreaded classroom drills in grade six and seven pushing mental calculations and

memorized times tables. All done from a well-meaning teaching perspective, but

to me, mentally paralyzing! By high

school, I was identifying myself to others as ‘hating math,’ or, ‘not a math

person,’ but to myself as, ‘not smart enough to do math.’

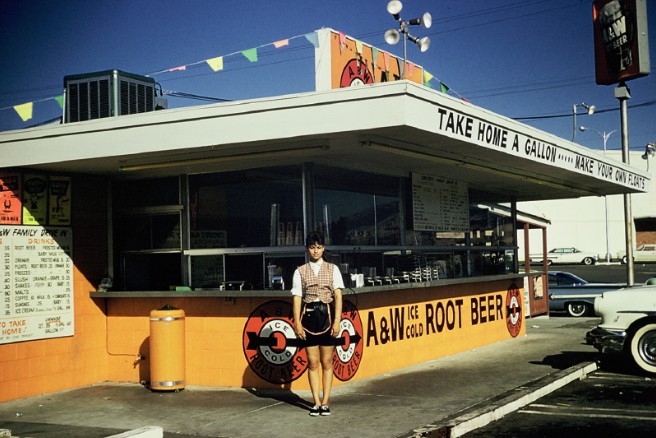

Reflecting on earlier moments with math, I did not have that dread or negative reaction as a kid. I remember how amazing Arithmetic was in

grade one. How the ‘aha’ light bulb went on while playing with Popsicle sticks

at the big Arithmetic table. Heaps of single Popsicle sticks, rubber-banded

bundles of ten Popsicle sticks, counting ten of those bundles out and stacking

them in a pile: 100 Popsicle sticks!

One bundle of ten and three singles: 13 Popsicle sticks! Okay, so I admit to this very day that I love Popsicle.

Especially the orange ones. Maybe that is because of the big, round, orange

sticker I got from Miss Mudry for my good work at the Arithmetic table.

It is true though, that after the dreaded mental math drills,

it took a while until I had another math-related Popsicle moment. One lazy

summer afternoon, eating Popsicle, I was idly throwing dice up in the air and

catching them after playing a table game on a blanket in the backyard with my

brother and sisters. A lovely breeze played through the hazel nut trees and the

dappled sun through branches sifted and shifted light as leaves fluttered. My

mind went back to

those dreaded mental math drills and before the walls of

shame had time to rise, the light and shadow, playing on those dice showed me

how the whole was made up of parts … how 5 was made up of 2 and 3 and if I

recognized the patterns of the dots—each dot a part of the whole—I could more

quickly arrive at an answer. Simply by visualizing patterns in the parts making

up a whole I could visualize the whole. Extrapolating from that popsicle

moment, I realized that I could ‘think in 10’s.’ I could move parts in and out to add in fives

and tens to estimate and calculate bigger numbers that were more difficult to add,

such as 27 and 58. I realized by adding 30 and 60, which was easy, and then

taking away 3 and 2, or five, was easy too. Suddenly grouping, or what I recognized

as seeing patterns of the parts making up the whole, made sense. Number sense!

Yeah for Arithmetic! Miss Mudry would have given me another orange sticker.Preparing to write the Calculations for Care givers course, I went on a hunt and scanned educational studies on developing number sense, or numeracy, in the era of math anxiety. I came across Dorothea Steinke’s work. Steinke understands the foundation of numeracy to "be part-whole thinking, which she defines as the ability to deconstruct quantities, keep track of the parts, put the parts back together in a different way to solve a math problem, and know that the answer makes sense" (Steinke, 3). Whatever numeracy was, I seemed to at least have an A, B, C understanding of it, thanks to a lazy afternoon throwing dice on a blanket in a nut orchard.

Numeracy, I learned, was a different way of looking at numbers from the math my high school and college profs represented. Their approach was to do

their utmost to prepare me to understand higher levels of math thinking—abstract conceptual math. Utterly beautiful but requiring a discipline and

passion that I was not able to give to it. Instead, numeracy is the ability to work

with numbers in the context of their purpose and use. Numeracy focuses on a

working relationship with numbers that are allies and colleagues in providing

what you need to know to do your job or live your life successfully. For

nurses, this would be the ability to calculate dosing safely and accurately.

For my other life with the horses and goats on Fox Song Farm, it is the ability

to figure out how much hay I need to get through the winter and determine if my

barn has space enough to hold that number of bales. It is also figuring out if I

can find

the money in my skinny bank account to pay for it. By the way, the

magic hay number is 10 tons, and yes, full up to the top, we have just enough room

to store the equivalent amount of small bales that make up 10 tons of breakfast

and dinner for our horses and goats (for 120 lb bales: 167 bales, rounded to

170 bales because I like round numbers). I'm still working on the bank account numbers.

Although I admire the mental athletics of mathematicians, I am

a lazy-pants math person and prefer playing in the shallow end of the pool,

yes, with popsicle sticks at the Arithmetic table. Numeracy—number sense—is how

I approach problems requiring calculation. And, instead of seeing numbers as

alien species with inscrutable habits, I now greet them as representatives of a

specific quantity of something tangible. Counters. Containers of the ‘thing’ I

am trying to calculate.

A light-bulb moment I have witnessed in students is when

they recognize the simple truth that ‘1’ is made up of all the points on the

ruler from 0 to 1. ‘One’ becomes substance, not mere label. For in numeracy, we

are concerned with the amount of something very real and meaningful. If I can

reframe a person’s understanding of number from an abstract non-entity to the

thing being measured itself, that person’s math anxiety greatly diminishes.

For example, I met with a student who was having difficulty

recognizing when a calculation in pharmacology (medication dosage) was incorrect.

The usual teachings about estimating an answer first and comparing this to the

solution, or double-checking her answer by using the ‘is this reasonable?’

question, or backwards solving the question was not working for her. Without

thinking, I said, “Okay, from the label know that you have 4000 mg in the bottle

total. Let’s say instead that it’s 4000 beans you have in

there. Given the drug

prescription you have been given, how many beans are you going to administer to

your patient?”

This time, she was able to recognize that with her wrong answer,

she was going to be giving WAY too many beans! That student later soared

through her calculations final, getting the required 100% of questions right in

record time. “It’s all about the beans,” she said to me. “When I begin to get anxious,

I ask myself, ‘how many beans!’”

Many of us with math-terror need a new way of visualizing

numbers. If thinking of beans helps, so be it. In Stanislas Dehaene’s book, The

Number Sense, he mentions that many

people often attribute a sense of personality,

or identity, to specific numbers, especially the integers. For example, many

people see a specific color when thinking about a specific number. Dehaene

cites studies demonstrating associations between numbers and colors: “most

people associate black and white with either 0 and 1, or 8and 9; yellow, red,

and blue with small numbers such as 2, 3, 4; and brown, purple, and gray with

larger numbers such as 6, 7, and 8” (Dehaene, loc 1646). What a rainbow an intricate

calculus problem would be!

Other than ‘4’, which I do see as a pale red rather

shy fellow beside the flashier ‘5’ who wears a herringbone suit with a wide tie,

I don’t see colors when I work with numbers. I do, however, in solidarity with

many primary school children, see the shape of numbers as demonstrating a sense

of personality. For example, ‘8’ is clearly googly-eyes set sidewise, an

obvious snoop who is trying to be sneaky about it, and ‘0’ definitely looks like

the Kool-Aid man who similarly intrudes into most large numbers that are just

standing there minding their own business.

I think I may include time in the course for students to air

their feelings about numbers. It will probably therapeutic for me, too. I might

have some unspoken animosity toward ‘O.’ On the other hand, I quite like ‘3,’

who is peaceable and always open to things.

When it comes down to it, although math can be intimidating

to many, numeracy—numbers—are etched in the gray matter of our fingertips. They

are a part of how we order our daily lives, but more, they are intimately

connected with the way we think. We are, ultimately, bean counters in the

nicest possible way. We measure things: with our tools, our hands, our eyes. We

count on our fingers and on each other. We weigh broccoli in the grocery store as

well as the worth of a politician’s words. Number sense lies in uncovering the reason

behind our search for the representative set of numerals, reasoning out what we

need to know, and allowing our words and numbers to slide together.

I guess that is the starting point—as well as the final anticipated

outcome—of my little course. For students to uncover their own natural number

sense so they recognize what makes sense number-wise, and are thus safe, safe,

safe when calculating medication doses.

Beans. Popsicles. Dice. The Kool-Aid man. Here’s to our collective

movement from math terrors to visualizing a rainbow of happy integers.

References

Dehaene, S. (2011) The Number Sense: How the mind creates mathematics, 2nd ed.

Steinke, D. (May, 2008) Part-Whole thinking. World

Education. http://www.ncsall.net/fileadmin/resources/fob/2008/fob_9a.pdf